eXist provides its own XQuery implementation, which is backed by an efficient indexing scheme at the database core to support quick identification of structural node relationships. eXist's approach to XQuery processing can thus not be understood without knowing the indexing scheme and vice versa. Over the past years, two different indexing schemes for XML documents were implemented in eXist: while the first was based on an extended level-order numbering scheme, we recently switched to hierarchical node ids to overcome the limitations imposed by the former approach.

The presentation provides a quick overview of these developments. I will try to summarize the logic behind both indexing schemes we implemented in eXist, and point out their strengths and deficencies. Based on this foundation, we should have a look at some central aspects of XQuery processing and optimization.

The indexing scheme forms the very core of eXist and represents the basis of all efficient query processing in the database. Understanding the ideas behind it helps to understand why some query formulations might be faster than their alternatives and is certainly a requirement for those who want to work on improving eXist's XQuery engine.

The main purpose of the indexing scheme is to allow a quick identification of structural relationships between nodes. To determine the relationship between any pair of given nodes, the nodes themselves don't need to be loaded into main memory. This is a central feature since loading nodes from persistent storage is in general an expensive operation. For eXist, the information contained in the structural index is sufficient to compute a wide-range of path expression.

To make this possible, every node in the document tree is labeled with a unique identifier. The ID is chosen in such a way, that we can compute the relationship between two nodes in the same document from the ID alone. Ideally, no further information is needed to determine if a given node can be the ancestor, descendant or sibling of a second node. We don't need to have access to the actual node data stored in the persistent DOM.

If we know all the IDs of elements A and B in a set of documents, we can compute an XPath expression A/B or A//B by a simple join operation between node set A and B. The concrete implementation of this join operation will depend on the chosen labelling scheme. However, the basic idea will more or less remain the same for most schemes. We will have a closer look at join operations and their characteristics below.

As explained above, the indexer assigns a unique node ID to every node in the document tree. Various labeling or numbering schemes for XML nodes have been proposed over the past years. Whatever numbering scheme we choose, it should allow us to determine the relationship between any two given nodes from the ID alone.

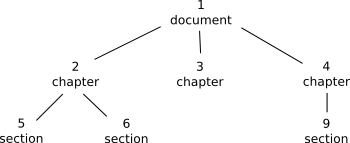

The originial numbering scheme used in eXist was based on level-order numbering. In this scheme, a unique integer ID is assigned to every node while traversing the document tree in level-order. To be able to compute the relationship between nodes, level-order numbering models the document tree as a complete k-ary tree, i.e. it assumes that every node in the tree has exactly k child nodes. Obviously, he number of children will differ quite a lot between nodes in the real document. However, if a node has less than k children, we just leave the remaining child IDs empty before continuing with the next sibling node.

As a consequence, a lot of IDs will not be assigned to actual nodes. Since the original level-order numbering scheme requires the resulting tree to be k-ary complete, it runs out of available IDs quite fast, thus limiting the maximum size of a document to be indexed.

Figure: Document with level-order ids

To work around this limitation, eXist implemented a "relaxed" version of the original proposal. The completeness constrained was dropped in part: instead of assuming a fixed number of child nodes for the whole document, eXist recomputes this number for every level of the tree. This simple trick raised the document size limit considerably. Indexing a regularily structured document of a few hundred megabyte was no longer an issue.

However, the numbering scheme still doesn't work well if the document tree is rather imbalanced. The remaining size limit may not be a huge problem for most users, but it can really be annoying for certain types of documents. In particular, documents using the TEI standard may hit the wall quite easily.

Apart from its size restrictions, level-order numbering has other disadvantages as well. In particular, inserting, updating or removing nodes in a stored document is very expensive. Each of these operations requires at least a partial renumbering and reindexing of the nodes in the document. As a consequence, node updates via XUpdate or XQuery Update extensions were never very fast in eXist.

So why did we stay with this numbering scheme for so long? One of the main reasons was that almost all of the proposed alternative schemes had other major drawbacks. For example, level-order numbering works well across all XPath axes while other schemes could only be used for child and descendant, but not the parent, ancestor or sibling axes.

In early 2006, we finally started a major redesign of the whole indexing core of eXist. As an alternative to the old level-order numbering, we chose to implement "dynamic level numbering" (DLN) as proposed by Böhme and Rahm (Böhme, T.; Rahm, E.: Supporting Efficient Streaming and Insertion of XML Data in RDBMS. Proc. 3rd Int. Workshop Data Integration over the Web (DIWeb), 2004). This numbering scheme is based on variable-length ids and thus avoids to put a conceptual limit on the size of the document to be indexed. It also has a number of positive side-effects, including fast node updates without reindexing.

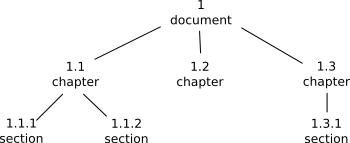

Dynamic level numbers (DLN) are hierarchical ids, inspired by Dewey's decimal classification. Dewey ids are a sequence of numeric values, separated by some separator. The root node has id 1. All nodes below it consist of the id of their parent node used as prefix and a level value. Some examples for simple node ids are: 1, 1.1, 1.2, 1.2.1, 1.2.2, 1.3. In this case, 1 represents the root node, 1.1 is the first node on the second level, 1.2 the second, and so on.

Figure: Document with DLN ids

Using this scheme, to determine the relation between any two given ids is a trivial operation and works for the ancestor-descendant as well as sibling axes. The main challenge, however, is to find an efficient encoding which 1) restricts the storage space needed for a single id, and 2) guarantees a correct binary comparison of the ids with respect to document order. Depending on the nesting depth of elements within the document, identifiers can become very long (15 levels or more should not be uncommon).

The original proposal describes a number of different approaches for encoding DLN ids. We decided to implement a variable bit encoding that is very efficient for streamed data, where the database has no knowledge of the document structure to expect. The stream encoding uses fixed width units (currently set to 4 bits) for the level ids and adds further units as the number grows. A level id starts with one unit, using the lower 3 bits for the number while the highest bit serves as a flag. If the numeric range of the 3 bits (1..7) is exceeded, a second unit is added, and the next highest bit set to 1. The leading 1-bits thus indicate the number of units used for a single id. The following table shows the id range that can be encoded by a given bit pattern:

| No. of units | Bit pattern | Id range |

| 1 | 0XXX | 1..7 |

| 2 | 10XX XXXX | 8..71 |

| 3 | 110X XXXX XXXX | 72..583 |

| 4 | 1110 XXXX XXXX XXXX | 584..4679 |

The range of available ids increases exponentially with the number of units used. Based on this algorithm, an id like 1.33.56.2.98.1.27 can be encoded with 48 bits. This is quite efficient compared to the 64 bit integer ids we used before.

Besides removing the document size limit, one of the distinguishing features of the new indexing scheme is that it is insert friendly! To avoid a renumbering of the node tree after every insertion, removal or update of a node, we use the idea of sublevel ids also proposed by Boehme and Rahm. Between two nodes 1.1 and 1.2, a new node can be inserted as 1.1/1, where the / is the sublevel separator. The / does not start a new level. 1.1 and 1.1/1 are thus on the same level of the tree. In binary encoding, the level separator '.' is represented by a 0-bit while '/' is written as a 1-bit. For example, the id 1.1/7 is encoded as follows:

Using sub-level ids, we can theoretically insert an arbitrary number of new nodes at any position in the tree without renumbering the nodes.

Based on the features of the numbering scheme, eXist uses structural joins to resolve path expressions. If we know the IDs of all nodes corresponding to e.g. <article> elements in a set of documents and we have a second node set representing <section> nodes, we can filter out all sections being children or descendants of an article node by applying a simple join operation on the two node sets.

In order to find element and attribute occurrences we use the central structural index stored in the database file elements.dbx. This is basically just a map, connecting the QNames of elements and attributes to a list of (documentId, nodeId) pairs. Actually, most of the other index files are structured in a similar way. To evaluate an XPath expression like /article/section, we look up "article" and "section" in the structural index, generate the node sets corresponding to the occurrences of these elements in the input set, then compute an ancestor-descendant join between both sets.

Consequently, eXist does rarely use tree traversals to evaluate path expressions. There are situations where a tree traversal is without alternative (for example, if no suitable index is available), but eXist usually tries to avoid it wherever it can. For example, the query engine even evaluates an expression like //A/*[B = 'C'] without access to the persistent DOM, though A/* would normally require a scan through the child nodes of A. However, eXist instead defers the evaluation of the wildcard part of the expression and later filters out those nodes which cannot be children of A.

This approach to index-based query processing leads to some characteristic features:

First, operations that require direct access on a stored node will nearly always result in a significant slow-down of the query - unless they are supported by additional indexes. This applies, for example, to all operations requiring an atomization step. To evaluate B = 'C' without index assistance, the query engine needs to do a "brute force" scan over all B elements. With a range index defined on B, the expression can again be processed by just using node IDs.

Second, the query engine is optimized to process a path expression on two given node sets in one, single operation. The join can handle the entire input sequence at once. For instance, the XPath expression //A/*[B = 'C'] is evaluated in a single operation for all context items. Also, the context sequence may contain nodes from an arbitrary number of different documents in different database collections. eXist will still use only one operation to compute the expression. It doesn't make a difference if the input set comes from a single large document, includes all the documents in a specific collection or even the entire database. The logic of the operation remains the same - though the size of the processed node set does certainly have an impact on performance.

This behaviour has further consequences: for example, eXist prefers XPath predicate expressions over an equivalent FLWOR construct using a "where" clause. The "for" expression forces the query engine into a step-by-step iteration over the input sequence. When optimizing a FLWOR construct, we thus try internally to process a "where" clause like an equivalent XPath predicate if possible. However, computing the correct dependencies for all variables that might be involved in the expression can be quite difficult, so a predicate does usually guarantee a better performance.

Unfortunately, many users prefer SQL-like "where" clauses in places where an XPath predicate would have the same effect and might even improve the readability of the query. For example, I sometimes see queries like this:

which could be reduced to a simple XPath:

Finally, for an explizit node selection by QName, the axis has only a minimal effect on performance: A//B should be as fast as A/B, A/ancestor::B or even A/following-sibling::B. The node set join itself accounts only for a small part of the processing time, so differences in the algorithm for parent-child or ancestor-descendant joins don't have a huge effect on overall query time.

eXist also has a tendency to compute node relationships bottom-up instead of top-down. Queries on the parent or ancestor axis are fast and it is often preferable to explore the context of a given node by going up the ancestor axis instead of traversing the tree beginning at the top. For instance, the following query uses a top-down approach to display the context of each match in a query on articles:

for $section in collection("/db/articles")//section

for $match in $section//p[contains(., 'XML')]

return

<match>

<section>{$section/title/text()}</section>

{$match}

</match>

This seems to be a rather natural way to formulate the query, but it forces eXist to

evaluate the inner selection $section//p[contains(., 'XML')] once for every

section in the collection. The query engine will try to optimize this a bit by caching

parts of the expression. However, a better performance can be achieved by slightly

reformulating the query to navigate to the section title along the ancestor axis:

for $match in collection("/db/articles")//section//p[contains(., 'XML')]

return

<match>

<section>{$section/ancestor::title/text()}</section>

{$match}

</match>

As of May 2006, the redesign of the database core is basically complete and the code is to be merged into the main line of development. The ability to update nodes without reindex has a huge performance impact for all applications that require dynamic document updates. The annoying document size limits are finally history.

We are still not running out of ideas though. Our recent redesign efforts will be extended into other areas. Concerning the database core, there are two major work packages I would like to point out:

First, the indexing system needs to be modularized: index creation and maintenance should be decoupled from the database core, making it possible for users to control what is written to a specific index or even to plug in new index types (spatial indexes, n-gram ...). Also, the existing full text indexing facilities have to become more extensible to better adopt to application requirements. The current architecture is too limited with respect to text analysis, tokenization, and selective tokenization. Plans are to replace these classes by the modular analyzer provided by Apache's Lucene.

The second area I would like to highlight is query optimization: currently, query optimization does mainly deal with finding the right index to use, or changing the execution path to better support structural joins. Unfortunately, the logic used to select an execution path is hard-coded into the query engine and the decision is mostly made at execution, not compile time. It is thus often difficult to see if the correct optimization is applied or not.

What we need here is a better pre-processing query optimiser which sits between the frontend and the query backend. Instead of selecting hard-coded optimizations, the new optimizer should rather rewrite the query before it is passed to the backend, thus making the process more controlable.

Also, a good part of the remaining performance issues we observe could be solved by intelligent query rewriting. We indeed believe there's a huge potential here, which is not yet sufficiently used by eXist. Though node sets are basically just sequences of node ids, processing queries on huge node sets can still pose a major problem with respect to memory consumption and performance in general. Query rewriting can be used to reduce the general size of the node sets to be processed, for instance, by exploiting the fact that eXist supports fast navigation along all XPath axes, including parent and ancestor. Those parts of the query with a higher selectivity can be pushed to the front in order to limit the number of nodes passed to subsequent expressions. This can result in a huge performance boost for queries on large document sets.